The un-dying profession

/A sun-scented breeze sweeps off of Wallowa Lake in Northeastern Oregon, wafting through the great ponderosas and up the slopes of the Eagle Cap mountains, passing as it does a rare gathering of a dying breed.

I’m not even talking about the wildlife, though there’s that. The deer may be plentiful in the park near the lake, but most others are barely hanging on. And so, it is for us—the writers. The summer intensive of my master’s in fine arts program begins with the writers’ conference called Fishtrap, which takes place at the Wallowa Lake Lodge each summer. This year, it’s scrambling to make up for thousands of dollars in cuts to arts funding even while most of the attendees pay hefty fees to attend.

I can’t guess exactly how the other writers feel, though the atmosphere feels a bit strained. No one mentions politics from the podium, except with oblique calls for donations to make up for the budget cuts. We’re now living in a country where writers lose their jobs or encounter blackouts for criticizing fascist secret police operations, a gold-encrusted wannabe dictator or a genocide funded largely by our taxes. We’re also living in a time when AI threatens to take over what few writing jobs are left.

While I don’t know what most of the attendees think, my fellow grad students talk. Some say they just want to focus on writing “for self-expression.” Those pretend that jobs and publishing don’t really matter. Maybe they don’t have student loans or rent to pay. But others glance sideways and grimace when the subject comes up.

We’re students gearing up to enter a field that may well be going the way of blacksmithing. Many of us are taking out substantial student loans to do so. And none of us really wants to acknowledge it.

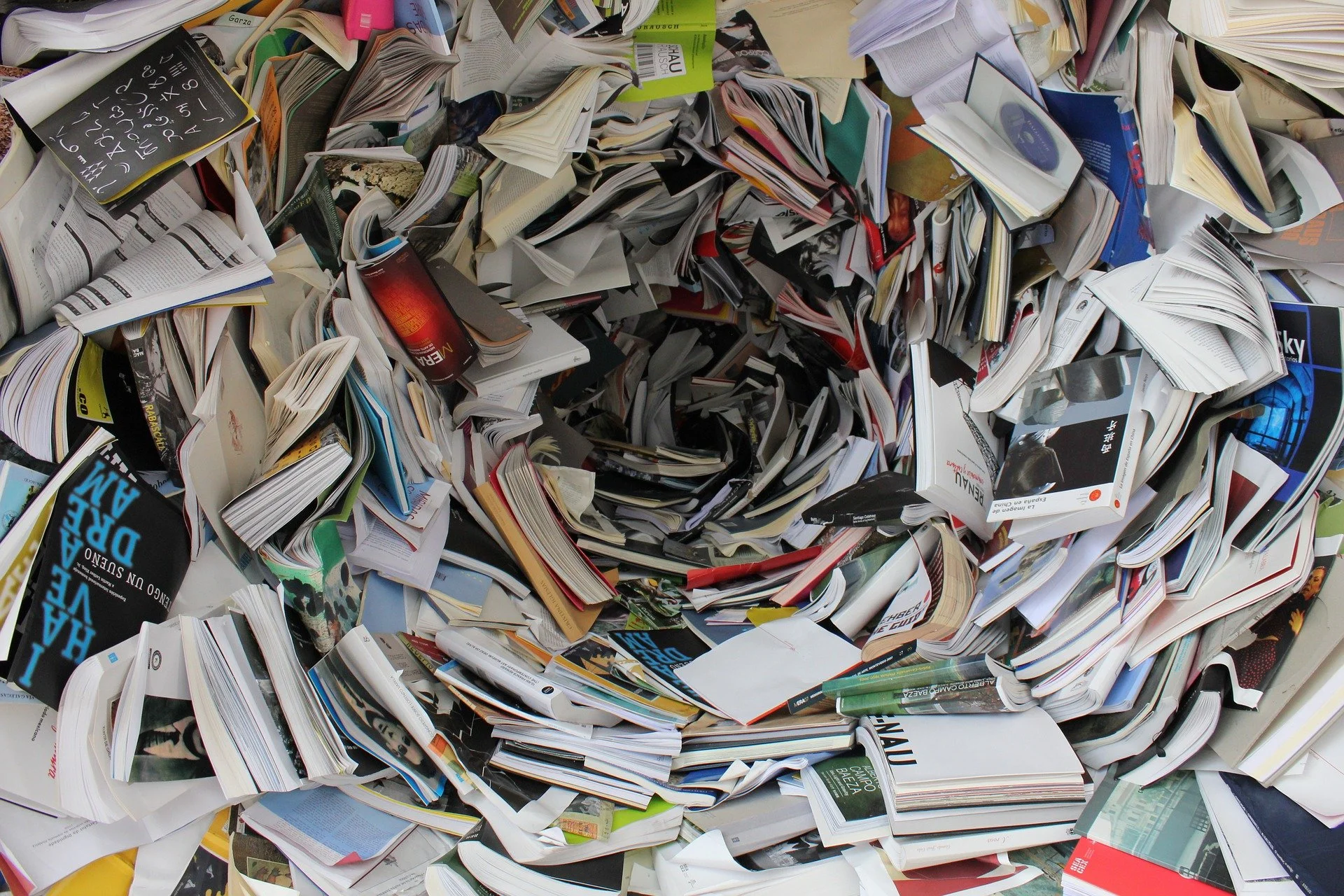

Image of books spiraling into a black hole - via pixabay

Right now, free versions of AI can write a business letter, press release or high-school-level essay better than 80 percent of the population. Teachers are in despair, trying to figure out how to curb the rampant use and abuse of AI by students to get around assignments that are meant to teach the skills to become part of the 20 percent who use words creatively and originally… and thus better than AI.

And yet, one has to wonder. Will there come a time when even creative and original writing is produced (or simulated) by some of the better AI systems, and even the best writers—the “masters” of the craft--will become obsolete?

The sense of quiet despair is palpable along the lakeshore. Is it among my classmates or just in my own head?

After we return to the dry, air-conditioned university classrooms following the Fishtrap conference, a professor asks how many of us have submitted to literary magazines recently. There’s an uncomfortable silence while we all avoid her gaze. We’re graduate students, not fifth graders, but no one wants to be on the spot for this one. She’s clearly disturbed by our response. She expected some of us to be slacking. But all of us?

We love to write. We’re all passionate and full of ideas. We are ravenously hungry for someone—our classmates, our professors, our parents, anyone—to read what we write, but we keep that quiet. It’s uncool to be too desperate. The biggest reason we aren’t submitting to magazines is the pervasive sense that it won’t matter, that we won’t get published in anything that anyone reads, that few people read books or literary magazines these days, that no one makes a living writing anymore unless they’re famous.

The bottom line is that there are too few writing jobs and too few readers and far too many of us.

Statistics say 99 percent of publishing funds go to celebrities and established authors. That leaves only 1 percent for the rest of us. And AI is rapidly gobbling up the crumbs of writing jobs that have traditionally been ours to divvy up between the masses of hungry, highly skilled and yet unknown writers.

Twenty percent of the population can write well enough to draft a decent statement. Probably 10 percent can write creatively. Five percent can craft a publishable book. Five percent of the English-speaking population is a lot of people (about 18 million people at the moment).

Heck even the 1 or 2 percent who are truly talented and committed add up to a lot of people. And writing jobs have never been plentiful. According to statistics only 0.03 percent of the working population makes their living primarily from writing.

So, that’s the reason for the awkward avoidance, but we keep the mood positive. We laugh in the teeth of the storm that threatens to wipe us off of this sketchy professional sandbar.

How can storytelling be a dying trade?

Storytelling is as old as humankind. I mean prostitution might be the oldest profession, but only because it predates our species. I’ve read archeologists who speculate that it is storytelling--not tools or language or fire--that differentiates us from animals. And that’s nothing against animals, just that their form of storytelling might not provide us with that satisfying zing of a complete story—curiosity, concern, need, resolution.

Will we really be okay if AI tells the stories from here on out, if people who want to write, just write for their own desk drawers or computer files, and learn to accept the lack of response?

Some people might think that’s okay.

But there’s a fundamental reason why I don’t agree. Stories are good and useful and even entertaining, but most importantly, stories are how we develop empathy. We come to see the world through the experiences of others from the time we’re babies listening to others talk about experiences or people they know. But if we’re lucky, we’re also read to, and we learn to read. We watch movies and today we go online. And mostly what we find is some form of story.

A lot of the stories today are essentially advertisements, whether for products, people or ideologies. They manipulate emotions and often shut down empathy. That’s largely because they claim to tell “your” story, the reader’s or viewer’s story. Whether oral or written, factual or fictional, stories about other people’s experiences give us little windows into other worlds and hence empathy.

And empathy is the one thing that has kept human society largely stable and livable, through all the political, military and social storms of the millennia. When things get too far out of balance, it’s empathy that brings us back. But today, increasingly there are those who are losing empathy, and I think it’s a story deficiency.

So, while we writers feel lost in the winds of the market these days, while I don’t know how we’re going to make a living at this, I know that we’re on the very frontlines of what our world most needs. We are the storytellers and whatever we write, even it isn’t earthshaking, even if it isn’t the greatest thing ever written, is essential and momentous.

The stories we write give brief glimpses into worlds that are different from a reader’s world in some way. Story must grip the reader and pull them into that different world to be effective. That’s one reason why stories must be entertaining. It’s not an added benefit. It’s essential.

So, skill does matter. We need to learn from one another, from conferences, from school, from writing groups and workshops, from copious reading and a ton of practice writing. But we must also keep the stories coming.

Because the world needs stories. This world with Empathy Deficiency Disorder needs writers.