Getting past the beginning of a novel - Advanced writing tips

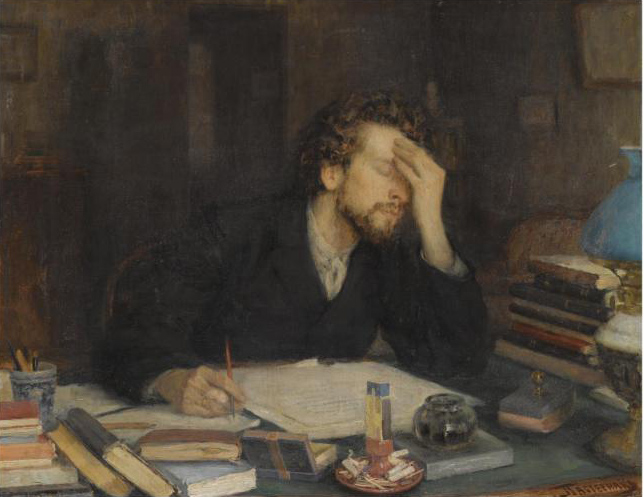

/So you’ve got a bodacious idea and you’ve written the first 20,000 or 30,000 words! You’ve got the gumption to start and the grit to put your butt in the chair and write through the wee hours of the morning or on your coffee breaks or whenever it is you have manage to squeeze in your writing time.

Congratulations! You’ve already beat out 99.75 percent of the competition. A lot of expert writing coaches like to quote the “Five percent rule.” The five percent rule says that of all the potential novel writers with an idea only 5 percent of them will ever start on it. And only 5 percent of those who do anything with their idea will make the time and discipline themselves to sit down and write regularly.

Creative Commons image by Misticsartdesign via Pixabay.jpg

I’m not sure if the numbers are actually that exact. But if you’ve reached this point, the end of the beginning of a novel, you have fortitude and courage. That’s undeniable.

And you have also just run into the steepest and scariest writing hurdle yet. According to the five percent rule, getting past the beginning should only cull out another 95 percent of the prospective authors out there, but this one feels bigger to a lot of us somehow.

Maybe it is because the people who didn’t make the first five percent cut really weren’t serious at all, so there was no pain involved. They just had an idea and didn’t pursue it. And the people, who didn’t get around to making a real start and didn’t manage the discipline or time to put their butts in their chairs. didn’t really sacrifice anything beyond mental anguish and a fair amount of whining.

On the other hand, the writers—yes, now really anyone who got this far is a writer—who falter at around the 30,000 word mark have worked hard. They’ve disciplined themselves, made real sacrifices to get the time to write and faced down fear and shame. And still… only a few will make it.

Writing coaches are supposed to make it seem like all the others will fail but you personally are the star who will not. I’m not making that call. You’re one reader and the bitter reality is that if one hundred writers at this stage of a novel read my blog, only about five of you will actually finish that novel. Fewer yet will ever see it published.

BUT… (And this is a big but.)

These statistics are about the novel, not about you. Most writers—I might even say, “hopefully all writers”—will start at least one novel they toss before they finish their first book. If you don’t, how do you learn and become an awesome writer?

We need ten thousand hours of writing to make a master, just like every skilled craft or art. So, if your novel falls by the wayside, that doesn’t mean you fail as a writer—just that you need to succeed with a different novel.

But this post is for those who have an idea they are convinced is a winner, those who have reached the end of the beginning and have the proverbial genitalia to keep on.

Let’s face it. It’s heavy going. No one gets past this one without some sweat, tears and likely some blood, whether fictional or actual.

If you are an expert plotter and have spent years on world building and have a detailed storyboard, maybe you have no idea what I’m talking about and you’re sailing through your manuscript without any trouble. But then again, if that were the case, you wouldn’t be reading this post.

If you’re like me and most other intrepid wordsmiths, you know the dreaded 30,000 word marker. Very possibly you’ve been here before. Maybe several times. And it might as well be the grim reaper.

There is something about reaching this point in a manuscript that makes writers wilt like that houseplant you forgot to water since you started this novel. No, you didn’t just run out of gas. It happens to all of us.

You start with an exciting idea and all the enthusiasm that goes along with it. There is very likely at least one early scene and possibly an ending and several other scenes firmly in your head before you start. You have a character or characters you like, a great setting and a unique premise. That can get you through 10,000 words without breaking a sweat.

You’ve got the opening description, the initial action and the premise to describe. In short, you’ve got clear goals that anyone with a couple of years of dabbling in writing can handle.

But I hate to break it to you. That’s the easy stuff.

Beginnings are important and must be brilliant and all that, but you know you can go back and edit, so you probably didn’t sweat rivers over it. Now, however, things get hairy.

You get to a certain point in writing your novel (usually somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 words depending on the type of plot you’re using and how much plotting you did early on) and you suddenly feel like you’re slogging through thick mud while carrying a fifty-pound pack.

How did this happen? You didn’t start out carrying a pack. Did all that positive energy just evaporate? Are you just a wimp without staying power?

No and no.

There is some small comfort in knowing that your exhaustion is completely justified. And it isn’t just that you’ve been cooped up in your basement staring at a screen for too long, although if that’s the case, remember that pacing yourself applies to writing as much as it does to running a marathon.

The 30,000-word marker is a different sort of exhaustion though.

Here’s the first key to getting through it: That fifty-pound pack is real.

OK, you can’t actually weigh it on a scale. But you are carrying a massive load after writing 30,000 words. You are carrying around in your brain all the bits and pieces, character traits, setting details and subplots that you subconsciously or consciously know you are going to need to remember later on. Depending on how many notes you’ve been keeping and how organized you are, this mental burden can be enormous.

Hopefully, even if you’re a write-by-the-seat-of-your-pantser, you have written down some notes about your major characters and main plot, at least the basics up until now. Pantsers are more likely to collapse at this point than plotters. It is one of the places where plotters can be justified in a bit of their smugness.

But plotters will have a burden too. Even if you write everything down scrupulously, you will be memorizing where you wrote what and how to find each piece of information. And there are always details you didn’t put in your notes, which is why your notes are not actually the novel, though their word count may be pushing a close second.

So, the first thing to do when you feel the sluggish doldrums at the end of the beginning descend upon you is to update your notes. Even if you’re an avowed pantser, now is the time to do a bit of plotting. Write character sketches if you haven’t yet. Make an outline of your plot or a story board, if at all possible. As you put down some of these burdens on paper, you will feel lighter.

If you have extensive notes, look through them. Make sure they are organized and remind yourself where to find things. Think through any plot holes that may have cropped up. Untangle and discard what has turned out not to be useful. Lighten the load.

The end of the beginning is also a good time to take a break from writing if you’re an intensive writer, spending hours writing each day. Get out in nature, spend some time with people or sleep all the hours you want for once, whichever meets your needs.

But don’t let go entirely. Many a good book has died because the writer went on a break at this point and didn’t actually come back. The break may feel way too good.

Set a limit or a deadline to get back at it. And then sit down and get back into it, no matter what.

OK, not entirely “no matter what.” As I said before, some projects need to die. Every writer needs to leave a few unfinished novels on their creative compost pile. So, don’t break yourself on something you have realized wasn’t a keeper. But if you are still convinced this is a keeper, put your head down and power through.

That is the third thing—and possibly the most crucial—about the end of the beginning. To some extent, you just have to push through this difficult time. It is likely that your plot or your characters are more complicated than you thought. You’ve realized you need to go back and change some things. Or you’re worried because you still haven’t figured out some major plot points coming up.

Whatever the specifics, this is a tough stretch. It’s uphill and there is no second wind yet.

Remember again that you can edit later. Keep in mind that this is normal for writers. It’s a natural part of the process of writing a novel. Take your best shot at how the plot needs to go and write it.

When you get to the 50,000- or 60,000-word mark and those last few puzzle pieces drop into place in your plot conundrum, you can go back and fix whatever you’re messing up now.

Yes, puzzle pieces dropping seemingly of their own accord happens far more often than a purely rational view of the writing process would indicate. And yes, you are messing things up at this point. It’s pretty much impossible not to. Don’t fret about it.

Getting past the end of the beginning is almost always messy or rugged or both. But by putting down some of your mental burden, taking a carefully limited break and pushing through the urge to throw it all in the recycling bin, you can crawl over this hurdle.