Self-respect and the old lady in purple

/“I’m too old to be respectable,” the woman in the overlarge purple dress cackles.

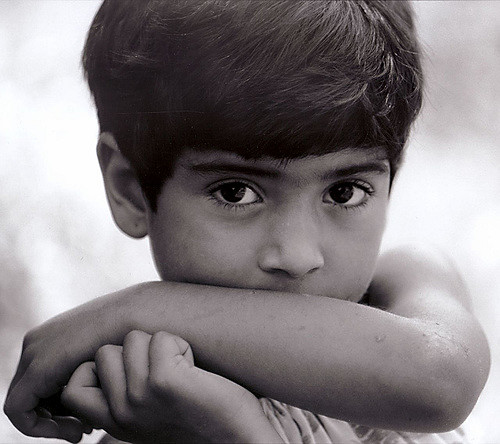

Creative Commons image by Moyan Brenn

She reminds me of the poem When I’m an Old Woman, I Shall Wear Purple, which my mother framed and put by the bathroom sink in my childhood home.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever been what they call respectable,” I reply and grin shamelessly.

“Just so that’s settled,” she brushes wispy hair out of her eyes and crosses the road on wobbly legs.

I look after her and think on “respect.” As the year turns round to the autumn, I am always reminded of elders and the question of respect.

I understand what the old woman means. She is too old to be considered “respectable” in this particular society, a society where “respectable” means successful, solid, emotionally contained, self-reliant and standard in appearance. It isn’t false modesty. She really is too old for that.

She cannot fulfill the requirements anymore, if she ever could. And I can’t fulfill them now, even though I'm not that old. My appearance is non-standard, no matter what I do. It isn’t that I couldn’t wear dark glasses to hide my strange-looking eyes. I see even worse with dark glasses, but I still could. Many people do hamper themselves physically for the sake of respectability.

No, it is more a general constitutional inability. I have tried for a standard image and I can hold onto it for a day if I really have to, but over the long-term... it just will not stick.

And being emotionally contained. Well, that too. I can fake it, but only for so long.

I am not successful by most measures. I don’t have a great career and my wealth is only just sufficient for a modest, environmentally friendly lifestyle. As for self-reliance… That is something I have thought about a lot recently because it is often listed as one of the key components of self-respect.

I suppose it depends on what you mean by self-reliance. Today it is often used to mean a person who needs no one else, who may help others but never needs their help, who is so strong in self that while they may enjoy the company of others, they don’t need it. They love themselves and thus don’t truly need love from outside.

I have a confession to make as a spiritual person. I don’t believe in that concept of self-reliance.

Creative Commons image by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

It isn’t that I’m against working hard and building your own life, being an adult and standing on your own two feet (or wheels as the case may be). I am all for the independent spirit. And I agree that you often have to “be your own best friend,” i.e. get yourself the gifts you wish others would get you and make time for self-care.

But I don’t believe that real self-reliance actually exists. It is like how the ranchers who took over a federal bird refuge near my childhood home in Oregon last winter claimed to be rugged, self-reliant pioneers in the wilderness, asking for no handouts and insisting that others should be the same and thus abolish “big government.” And yet their key demand was to be allowed to use federal land for their cattle free of charge.

And then to top it all off, they asked to be given food while they illegally occupied the buildings at the bird refuge.

Those who believe they are self-reliant are invariably simply unaware of the beings they rely upon. Many great, pioneering businesses were built through environmental degradation, on the backs of others. Not self-reliance but reliance on stolen resources. Many who claim to be self-reliant had advantages they don’t even notice, privileges they assume everyone has but which actually rely on others.

I grew up in a remote, rural area. We grew and raised a good deal of our own food. In a dry land, we had our own well and our own water. The winters could be so harsh that we were often cut off from the nearest tiny town of 250 souls by snowdrifts.

One winter--the winter of the Great Ice Storm--we heard on the radio that our area was considered a humanitarian disaster area and officials were concerned that we must be starving because we had been isolated for a week and the electric power was down for many days. We weren’t starving. We had pantries and root cellars, as did our neighbors. My father and other men put on skis and went around to the neighbors to make sure no one was starving and no one was—not even the ancient man who lived alone with his goats.

Sounds pretty self-reliant, right?

Well, except for the part about checking on one’s neighbors. I have lived in a dozen homes since then and I have never lived in a place where neighbors relied on one another so much as we did there. We never even thought about “self-reliance.”

Hunter-gatherer societies were built on community and mutual support. And rural communities are interconnected and generally much more supportive of their weaker members than are urban centers. We lived that reality, even though our neighbors were often not our best friends.

And then, of course, there was our well.

As I said, this was an arid land, officially semi-desert, even though we had pine and tamarack trees. The snow melt provides most of the water and it rains in the spring and then scarcely rains again for six, even eight months. A well in that country is a holy thing.

Our well was 60 feet deep. When I was a teenager, I once went down to the bottom of it because I was small enough and my father wanted to put in a new kind of pump. I calmly did the work I was asked to do down there with a headlamp and then I made the mistake of glancing up just for a second before pulling on the rope to signal that my dad could pull me out.

When they tell you not to look down when you’re up very high, you understand why. My father had told me not to look up and I was sure that was because he didn’t want dirt and sand from the walls to fall into my eyes. But when I looked up, I was gripped by utter terror.

It was night! I had not realized I had been down there so long. The moon was out, riding high and full in the sky. That was all my mind could think.

Then I realized that the moon was the opening of the well far above me. It looked so small 60 feet up that it was no larger than the moon in the night sky. I looked down again and gripped the rope as hard as I could. I was pulled up out of the well quaking with unreasoning fear and I never want to go down such a well again if I can help it.

But here’s the thing that I’ve never forgotten about that experience: someone dug that well.

Someone, long ago, before the time of electricity dug that well through rocky, hard mountain soil and lined it with perfectly fitted stones all the way down to the bottom. They had to spend a lot more time down there than I did.

My childhood home stood on the back of that anonymous stranger.

Sure, my parents bought the land and the well fair and square. But still… I never could forget the neat rows of stones laid so carefully 60 feet beneath the ground in that narrow shaft.

So, I believe in self-reliance in a different way. I believe in being able to rely on yourself. I know what I can do and what I can’t. I am good with water and I can swim in strong currents. I was once sure-footed climbing rocks and trees. Now that I am older I am not so sure and I know my own limits. I know that if I do ever have to go down a long, dark well again, I can. But I will not look up.

I know what my body, mind and emotions can handle. I can rely on that, including the weak spots. Self… reliance.

And I am not unconscious of the fact that my life is interconnected with others.

As for being respectable. That too has various meanings. What society today sees as worthy of respect is not necessarily what it has always been. There have been times and places where a person as old as the woman in purple would be respected for the achievement of having survived so many years.

I have my own version of respectability and that is self-respect. As long as you have your self-respect and you live up to your own standards, then you are respect-able in the only way that really matters.